Yoshio HIGUCHI

|

The Japanese Government-Labor-Management Meeting on the Labor Market and its Statistical Background

|

Even if the economy starts to recover and corporate earnings pick up, that will do little to help the average person if not accompanied by higher wages and salaries. Indeed, if it simply indicates that higher prices are lifting the economy out of a deflationary spell, all it would mean for most people is that times are soon to get even tougher.

We hear that the economy is turning around on support from “an entirely new dimension of monetary easing” and large-scale financial stimulus packages. Yet, without any increase in worker compensation, the benefits are sure to accrue mainly to big corporations and a handful of wealthy people, with perhaps a ripple or two extending out into the real economy. To break away from deflation and achieve sustainable economic growth, we need higher worker compensation and, as a result of that, stronger personal consumption and heavier facilities investment. We need a way to link the increases in corporate profits and retained earnings to something that will benefit the greater economy. The people want a raise, economic policymakers want a raise to happen, and both parties are becoming increasingly insistent about it.

In principle, labor negotiations in Japan are left to labor and management. These parties alone determine wages: the government has no direct say in the matter. This time, though, the government has gotten itself involved. While maintaining the doctrine that compensation is something to be determined by direct labor–management negotiation, the government is nonetheless working to impart a shared perception among labor and management that, particularly with regards to companies with strong earnings growth, it is time to pay workers more. For such initiatives, no fewer than five sessions of the Government-Labor-Management Meeting for Realizing a Positive Cycle of the Economy have been convened.

What set government policymakers on such an unusual course of action? What has been discussed at those meeting, and what kinds of agreements were reached? We can be sure that statistics played a particularly large role in these discussions. How? In this paper, I examine such statistics and discuss the contextual background they formed for the Government-Labor-Management Meeting as one of its members.

Productivity and worker compensation in Japan, Europe, and the United States

The Japanese government injected itself into labor–management wage negotiations once before, in 1975, during the immediate aftermath of the first oil crisis. The inflation rate had jumped to 32.9% the previous year, compelling policymakers to do something to break the inflationary wage/price spiral that was making life difficult for nearly everyone. On one hand, the government persuaded labor unions to tone down their demands. On the other, it implemented policies intended to support real income growth.

That episode, however, was the last direct government intervention into a private-sector wage/salary determination process. Since that time, policymakers have followed a de facto policy of leaving such matters to individual company and the union with which they negotiate.

With regards to Europe, notable here is the Wassenaar Accord (1982), a negotiated three-party (government, labor, and management) response to the double-digit unemployment rates that plagued the Netherlands in the early 1980s. The idea was to "share the pain" and, by that sharing, to reduce unemployment. Indeed, the vigor with which the Dutch economy responded to this initiative is remembered to this day. Here, labor agreed to forebear on wage demands, the government pledged to reduce taxes at the cost of cutting back on social services, and management vowed to maintain employment through work-sharing arrangements. This accord, credited with having significantly reduced unemployment and revitalizing the economy, would subsequently provide the framework for the Dutch-style employment system.

Admittedly, the Japanese economy currently faces a somewhat different situation. What the government seeks to do with this latest intervention is to impart a shared perception of a need to break the Japanese economy out of its deflationary spiral and attain sustainable growth or, more specifically, to make sure that both labor and management fully appreciate the necessity of tapping retained corporate earnings, which have been rising once again amid an economic recovery, to pay higher wages and salaries to employees.

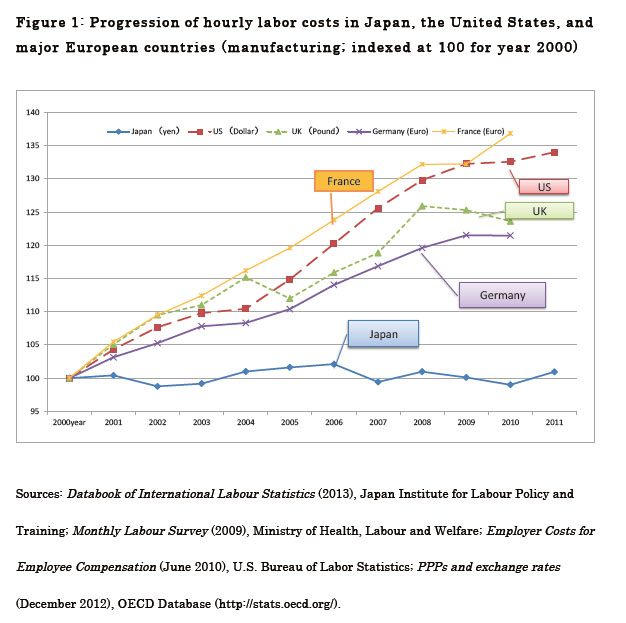

Japanese salaries and wages (total cash earnings) remain on a long-term downward trend. Indexing nominal hourly labor costs (manufacturing) for the year 2000 at 100, we find a 2010 value of 133 for United States, 137 for France, 121 for Germany, but only 99 for Japan (Figure 1).

It is true that Japanese economic growth slowed markedly over that period. In the decade before the first oil crisis the economy grew at average annual rates in excess of 10%. Then, within the so-called "bubble era" that extended to the late 1980s, real economic growth slipped to 5%. In the 1990s, it fell even further, to the 1% level. Similarly, nominal GDP peaked in 1995, remained essentially steady over the years that followed and, more recently, has actually been declining. Indeed, over the period from 2006 through 2010, the average annual economic growth rate for Japan was 0.4%, not much different from that of the United States (0.7%) and of five major Eurozone countries (0.8%). Despite this similarity, we can see from Figure 1 that salary and wage growth in Japan has been far less than that in the West.

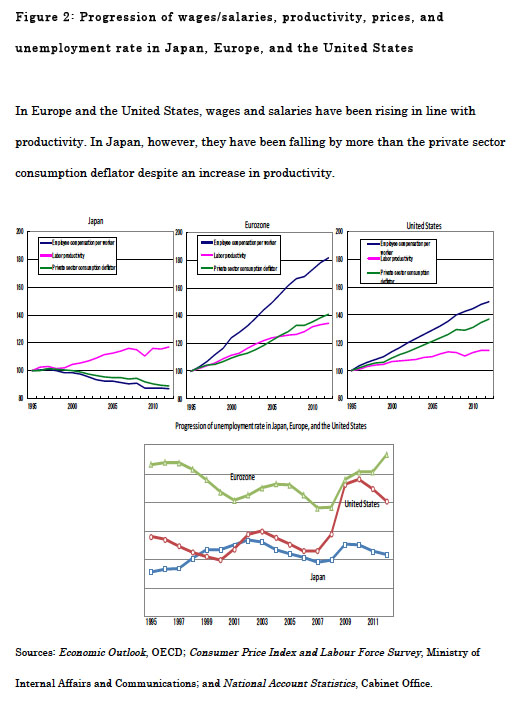

Figure 2 shows the progressions of per-employee compensation and labor productivity and a private sector consumption deflator for Japan, the Eurozone, and the United States. With regards to the Eurozone, we see that per-employee compensation has risen considerably more than either labor productivity or the consumption price index over the past 15 years. The same can be said for the United States. In both cases, per-employee compensation has risen considerably faster than either labor productivity or the consumption price index. With regards to Japan, in contrast, we see that although labor productivity has risen by roughly the same amount as in the Eurozone, per-employee compensation has risen by far less or, more precisely, has actually fallen, by roughly 10%, from 1995. Again, we could say the pretty much the same thing with regards to United States. In short, we can clearly see that whereas wage and salary growth exceeds labor productivity growth in both the Eurozone and United States, in Japan, wage and salary growth has actually declined despite labor productivity growth at approximately the same rate as in the Eurozone and the United States.

Unemployment rates have been consistently low in Japan but high in the Eurozone and the United States. To put it another way, unemployment rates are high in the Eurozone and the United States, but in exchange those who do have a job there have benefited from strong wage and salary growth. In Japan, however, workers have benefited from employment stability but this has come at the cost of wage and salary growth.

From a variety of national data sources, we calculate employment adjustment speeds for the periods 1980–1994 and 1995–2007. For the United States, the speeds are a comparatively high 0.56 for the first period and 0.73 for the second. A useful feature of this value is that the inverse can be taken as the number of years it requires for corporate employers to shed excess workers (as they might wish to do during an economic downturn). That is, for United States, we see that it would have taken 1.78 years to “right size” the workforce in the first period and 1.37 years in the second. For Germany, the corresponding employment adjustment speeds are 0.17 and 0.72; that is, it would have taken German corporate employers 5.88 years and 1.39 years, respectively, to rid themselves of excess workers during the two periods. Here, we see that for both the United States and Germany, the employment adjustment speed was more rapid during the second period than during the first. For France, adjustment speeds were 0.53 and 0.42, corresponding to 1.89 years and 2.38 years. So, here we can say that French companies require considerably more time to shed excess workers than do their US counterparts.

What about Japan? Here, the employment adjustment speed for the period 1980–1994 is 0.08, which means that it would have taken 12.5 years to reduce excess employment. This speed increased, reaching 0.35 for the second period, a figure corresponding to 2.86 years. Yet, even at 2.86 years, it would still take Japanese corporate employers considerably longer to reduce their workforce than either their European or US counterparts. This, considered together with the wage and salary situation discussed earlier, can be interpreted to mean that Japan’s labor unions, in exchange for preserving employment, have paid the price of essentially abandoning their attempts to raise wages and salaries.

The pursuit of micro-rationality and the fallacy on Aggregation

Within all major European Union countries (with the notable exception of the United Kingdom), collective bargaining is advanced, and labor agreements concluded, through a centralized system that goes beyond individual companies to encompass countries and entire regions. This is done on an industry-specific level, with wages determined by skill level and applied across all companies within the industry. Any particular company operating within this framework cannot turn to wage cuts in an attempt to bolster its competitive position within some product market, and thus wages are shielded from competitive intensification (Suzuki, 2011). To restate this, however, not even a company in dire managerial straits can resort to pay reductions—management temptations instead turn to workforce reductions. This feature is common to centralized systems of wage determination.

Japan, in contrast, basically follows a decentralized system centered on seasonal wage negotiations (in spring) between individual company and its union. A characteristic of this system is that although wages tend to closely reflect the managerial condition of a specific company or the competitive situation of the market in which it operates, employment, on the other hand, tends to be preserved during economic downturns.

Japan is now cited as a classic example of this decentralized wage determination. There was, however, a time when the country was known for its "spring offensives.” In those offensives, nearly all companies would almost simultaneously enter into annual short-term bargaining sessions, with an industry-leading company first determining a wage hike and then nearly every other company in the industry following with a similar hike of its own, thus broadly diffusing pay increases throughout society as a whole. In recent years, however, competition with overseas rivals and other such developments have intensified the degree of inter-company competition, leading to situations in which a company with strong earnings growth will simply elect to pay a bigger bonus instead of increasing base pay. This diminishes the ripple effect of wage hikes at other companies and leads to a higher degree of individualization from one company to the next. Indeed, surveys carried out to determine just what company managers emphasize when considering revisions to their wage and salary structures show that although in the old days their primary considerations were a need to maintain broad market agreement and match pay hikes on the part of industry rivals, from the 1990s such concerns diminished, such that an increasing proportion of companies nowadays cite their own financial condition as a primary consideration.

With a centralized system of wage salary determination, it is not unusual for unions to forgo wage hikes, because if a union demands and secures a wage hike, it runs the risk of swelling the company's personnel costs and sapping its competitive strength to the point where it is no longer able to preserve employment. Conversely, within a highly liquid labor market, management is hesitant to lower wages significantly below market levels lest it drive the best employees into the arms of industry rivals. This acts to moderate downward pressure on wages. In countries, such as Japan, where the labor market is illiquid, there is relatively little worry of driving off good workers with low wages because in Japan it can take a long time to find another job and the switching costs are high. Thus, within such countries, wage and salary levels are increasingly likely to be used as a means to maintain company financial competitiveness.

That is, as the international competitive environment becomes more intense, individual labor–management bargaining teams will often play down wage negotiations out of an eagerness to strengthen competitiveness and protect in-house employment. Indeed, we even see some cases in which a company with strong earnings growth will refrain from wage hikes out of concern about the actions of industry rivals.

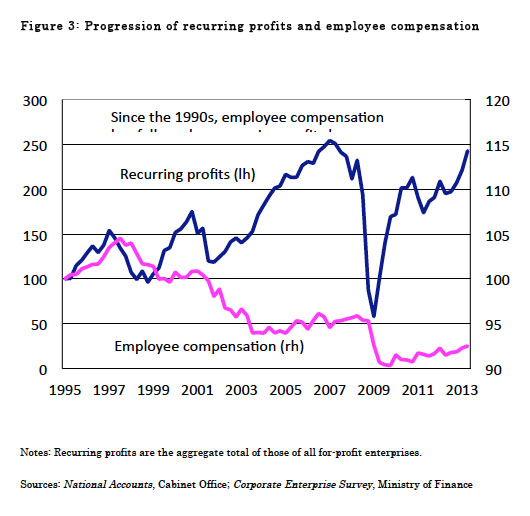

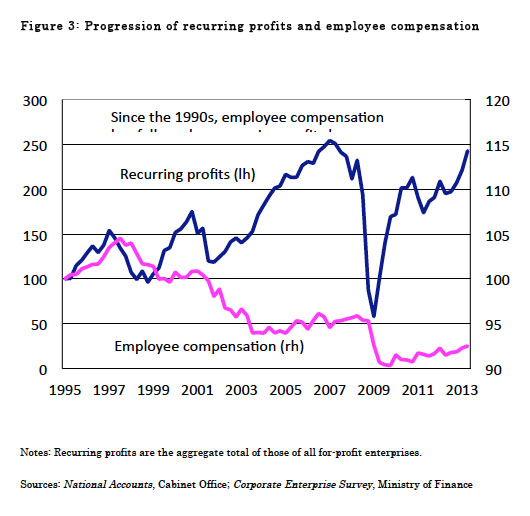

With regards to individual labor–management teams, there is a certain rationality to such attempts to reduce wages and protect employment. On a macroeconomic level, however, cuts to worker income have a negative effect on consumption demand. In Japan, this, together with a stronger yen, has acted to intensify downward pressure on wages, eventually producing a deflationary spiral. That is, wage and salary cuts have the short-term benefit of preserving employment, but as stagnant wages continue and begin having structural implications, this has a negative impact on demand and, eventually, even employment. Once such a pattern—lower prices followed by lower wages—becomes entrenched within the minds of both labor and management, an uptick in corporate earnings amid a spurt in the economy does not necessarily lead to an improvement in terms of employment or an increase in facilities investment; it may simply end up as an increase in retained earnings (Figure 3). This can be seen in the economic recovery from 2002, the longest such recovery in history. Back then, wages did not rise. We could find ourselves in a similar situation. That is, to transform a macroeconomic policy-driven economic revival into favorable conditions in the real economy (i.e., a clear break from deflation and a period of sustained economic growth), we need to somehow raise wages and salaries. It is this situation that led the government to call upon labor and management to participate in a Government-Labor-Management Meeting with the aim of achieving a virtuous economic circle.

|

Even a company benefiting from an improvement in profitability would be loath to raise its base pay—that is, to consent to a permanent wage hike—unless it had a good deal of confidence in the sustainability of an economic recovery into the future. On the other hand, as first propounded by Milton Friedman with his permanent income hypothesis (1957) and later confirmed by numerous researchers, bonuses and other transient hikes do only a little to encourage marginal consumption and not much to increase consumer spending. Instead, we must increase permanent income, and this is done by raising base pay, as by increasing scheduled earnings, providing periodic raises, and so on. Thus, with regards to creating a virtuous circle of sustainable economic growth, the issue comes down to the degree to which and the certainty with which base pay can be raised. Another important point, particularly amid a shift toward a sellers' market, becomes the extent to which wage hikes at one company ripple to other companies that are not recovering quite so rapidly, such as small and medium enterprises and firms strongly tied to regional economies.

One factor: lower wages

A look at the progression of wages by industry and employment type reveals that average wages have fallen substantially as a result of not only a slump in wages paid to individual workers within any specific category, but also an increase in the proportion of workers within low-wage categories. For instance, average wages in the manufacturing sector are generally higher and more stable than those in the service sector. However, in the manufacturing sector, the workforce has diminished, from slightly above 12 million workers 10 years ago to less than 10 million now. With regards to the service sector, productivity growth lags the domestic manufacturing sector and, in international comparisons, even lags the service sectors of other countries.

Here, one reason for the substantial drop in average wages is that the service sector now accounts for a high proportion of employment.

As in the manufacturing sector, raising wages in the service sector requires an underlying improvement in productivity. Simply raising wages without a corresponding productivity increase merely acts to reduce employment. This said, when we talk of improving productivity, we must specify that we are referring to added value productivity. There is also physical productivity, and an improvement in that would not do us much good because it would lead to lower prices and, by extension, lower added value productivity. In other words, we must do more than just improve productive efficiency, we must also work to raise the value of products and services. For this, innovation is required: the ability to provide products and services that are highly valued within the market and unmatched by any other. It is by this occurrence that it becomes possible to achieve sustainable wage hikes (Yoshikawa, 2013).

That need, too, was discussed at the Government-Labor-Management Meeting.

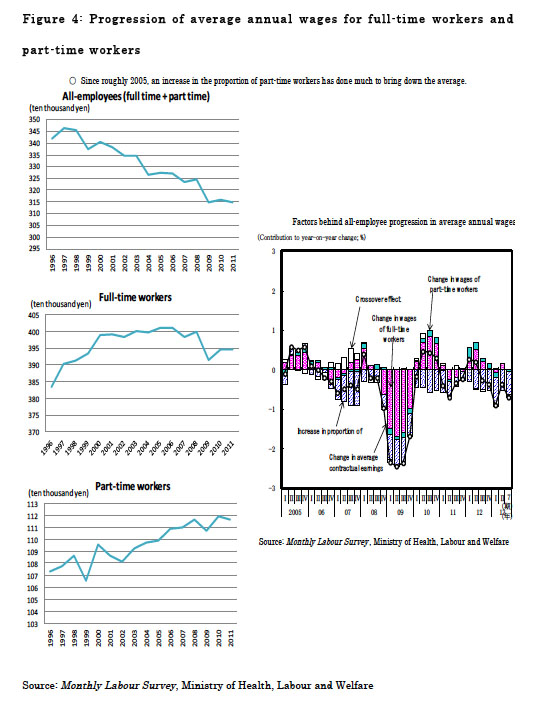

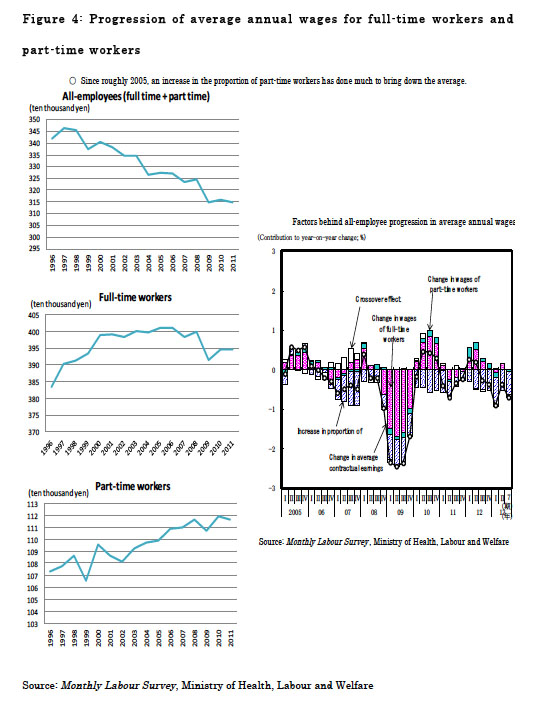

Within our shifting industrial structure, the primary factor driving down average earnings is a proportional increase in non-regular workers. Figure 4 shows the progression of annual contractual (i.e., fixed) earnings for all employees (full time plus part time). The chart on the right of the figure tracks the factors behind the change (all-employee progression in average annual wages). In the charts on the left, we see that the contractual earnings of full-time workers dropped substantially in the aftermath of the Lehman collapse (2008) but, excepting that disturbance, have remained essentially steady since 2000. On the other hand, the earnings of part-time workers have remained on a slight uptrend. Yet, despite this, we observe that the all-worker average earnings—that is, the sum of the two—is declining, as we can clearly see in the top chart. This is largely because of the increasing proportion of (low-wage) part-time workers within the mix. Indeed, a look at the right chart shows that of the various factors affecting the all-employee progression, the increase in proportion of part-time workers has had a particularly large effect.

|

One could look at this figure and reasonably conclude that the decline in average wages is in good part attributable to the relatively short working hours of part-time employees. If, however, we instead use data from the Basic Survey on Wage Structure (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare), taking non-regular workers (contract employees, fixed-term employees, agency temporary workers, etc.) in place of part-time employees and taking hourly standard (non-overtime) wages in place of annual contractual earnings, our conclusion is unchanged: a decrease in the number of regular full employees, combined with an increase in non-regular workers, has contributed greatly to the decline in overall hourly wages. Here, we confirm that to raise average wages, it is necessary to improve the working conditions of non-regular workers and, simultaneously, it is important to somehow provide more opportunities for employment as regular full employees.

The recent increase in non-regular workers is due not so much to an increase in the number of people taking on casual or day labor, but rather to a tendency for those who become non-regular workers to remain in that status for a long time (Labour Force Survey, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). According to a 2011 survey of employment contracts conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, those non-regular workers who were in positions that require a level of skill equivalent to a regular employee renewed their contracts an average of 7.42 times. As a result, 33.4% of those people have worked at their present employer for more than 5 years and 13.5% for more than 10 years. Even with regards to those in positions that do not require an equivalent level of skill (i.e., those that entail work that is simpler than what would normally be assigned to a regular full employee), the average worker renews his or her contract 6.63 times, and 26% have been at their present employer for more than 5 years. Although fixed-term contract employees by name, there are an increasing number of people who remain within that category for a very long time.

Even within the non-regular worker category, there are an increasing number of people who are not there by choice, but rather because they cannot find employment as a regular employee. These people—non-regular workers who would rather be formal employees—accounted for only 14% of all non-regulars workers back in 1999 but 23% in 2009. By employment type, the increase is most notable among agency temporary workers, up from 29% in 1999 to 45% in 2009, and is even substantial among contract employees, up from 29% to 34%. This, too, was a central point for discussion at the Government-Labor-Management Meeting. Specifically, how should we go about arranging a diverse set of regular employee positions, limited in work scope and geographical assignment, and, by that, create a framework to facilitate a shift to regular full-time employment for those who desire it (Higuchi, 2012)?

The necessity of skill development, higher added value productivity

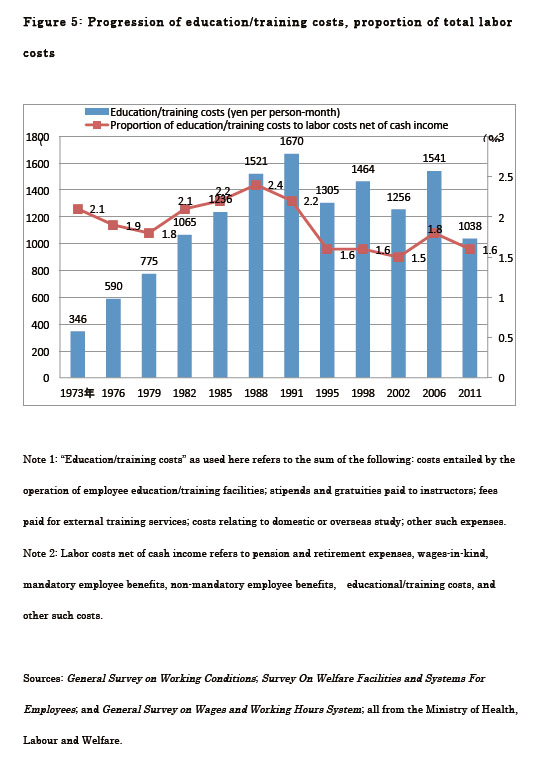

Corporations are working to limit personnel costs and, as they do so, they are cutting back on employee education and training. The forum also brought up this issue—skill development is not necessarily being promoted as it should be (Figure 5). Above, we saw that to achieve sustainable economic growth, we need to not only raise wages and salaries, but must also improve added value productivity to support those wage and salary increases. This necessitates capital investment; it also necessitates higher levels of vocational skills among the workforce. Here, some say that if the corporate sector somehow finds it difficult to provide adequate education and training on its own, then maybe the government should step in to help.

That, too, was proposed at the meeting.

Along with the issue of employment conditions discussed above, this can be a real problem for non-regular workers, in that such workers are not provided with any corporate-sponsored education or training opportunities and, as their vocational proficiency thus remains unimproved, just do not have the necessary skills to assume a position as a regular employee. Government participants viewed this as a particularly serious concern, promising at the meeting to partially subsidize the vocational development costs incurred by corporations that provide in-house training to non-regular workers and the labor employment costs incurred upon the conversion of such workers to regular employees.

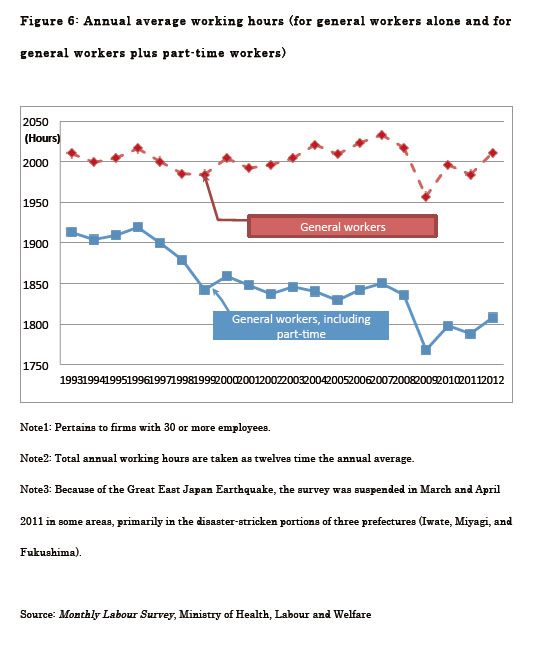

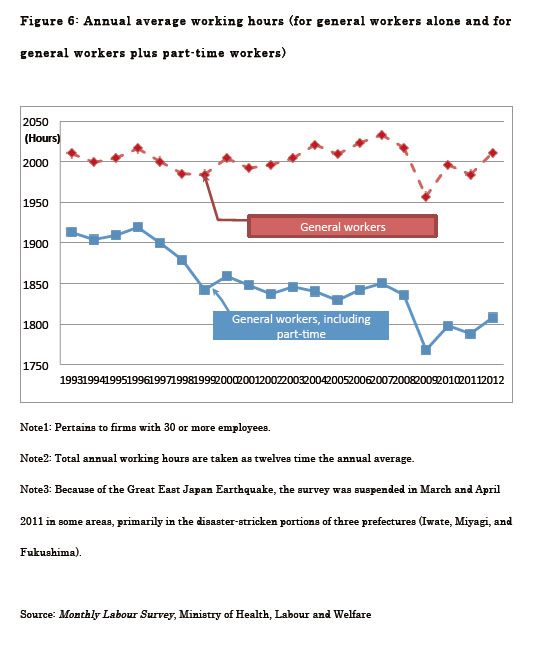

Pressure to hold down personnel costs has a strong effect on not only wages and salaries, but also on working hours, which are another important aspect of working conditions. When seeking to raise production, an employer often finds it easier to extend the working hours of its current workers than to hire additional workers. The issue here, of course, is whether this compels workers to work excessively long hours and, by that, thwart work–life balance initiatives to shorten working hours. Figure 6 shows the progression of average annual working hours. The figure for general workers plus part-time workers has indeed declined over the years. Twenty years ago, it was more than 1900 hours; now, it is down around 1800 hours. The leading factor behind this decline, however, is an increase in the number of part-time workers. Limiting the discussion to general workers (i.e., excluding part-time workers), we note very little change over the past two decades. Note too that within this period, the five-day workweek has become commonplace (previously, it was not unusual to also work on Saturdays). That the average number of working hours nonetheless remains unchanged means that people have been working longer work days and have been taking fewer paid vacations. Then and now, a fairly high proportion of the population works more than 60 hours a week. Many workers find that working such long hours has a deleterious effect on both their physical and mental health.

|

Faced with a population that is not only getting grayer but also fewer in number, Japan must arrange an environment in which anyone, regardless of gender or age, can work to the full of his or her ability and willingness; the maintenance of a good work–life balance is essential to this. Here, too, meeting participants agreed on the need for labor, management, and government to work together.

Labor and management efforts toward the realization of a virtuous economic cycle

In Japan, it is very unusual for the government to give specific guidance about the terms of employment reached through company-specific negotiation between labor and management. The government, in its belief that wage and salary hikes are necessary to initiative a virtuous economic circle, nevertheless went ahead with its call for labor and management to join it in discussion. Several agreements resulted.

For its part, the government agreed to support a tax regime that promotes income growth, to abolish a Special Corporation Tax for Reconstruction one year ahead of schedule, and to implement a variety of other support measures. Labor and management reached agreement as well, to the effect that, within a government-arranged environment toward the attainment of a virtuous economic circle, they would work together to link pay increases to corporate earnings while fully considering such matters as the economic situations of specific companies and developments relating to the economy, corporate earnings, and prices. Thus, in Japan, terms of employment are to be left to negotiations between individual labor and management, without any compulsion from the government. While it remains to be seen to what degree these agreements will be observed in the future, we nonetheless consider them highly significant for their demonstration that labor, management, and government have arrived at some shared vision of the attainment of a virtuous economic cycle. Again, we will be following closely to see to what degree these agreements will be honored by the various parties.

In the process of reaching these agreements, statistics played a highly significant role. Indeed, when participants would debate one issue or another, they would generally be debating about statistics, or, at least, centering their arguments on them. In this manner, the Government-Labor-Management Meeting also underscored another important point: the importance of “statistical quality,” particularly as it relates to assuring the comparability of data across countries and the coherence of information across data sets.

References

Suzuki, H., “Recent Trends in Collective Bargaining and Wage Determination in Major EU Countries: Continuity and Changes,” The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies, No. 611 (2011).

Friedman, M., A Theory of Consumption Function, Princeton University Press (1957).

Higuchi, Y., “The Dynamics of Poverty and the Promotion of Transition from Non-regular Employment to Regular Employment in Japan: Economic Effects of Minimum Wage Revision and Job Training Support,”The Japanese Economic Review, Vol. 64, No. 2 (2013).

Yoshio HIGUCHI is Professor of Business and Commerce at Keio University in Japan. Professor Higuchi's research is mainly concerned with labor supply, labor mobility and employment policy. His research interests include the labor supply behavior of women and older workers, and employment practices in Japanese firms from the viewpoint of human capital theory. He has published articles in the Journal of the Japanese and International Economy and the Journal of Population Economics, among others.

Professor Higuchi is Visiting Researcher at the EHESS France-Japan Foundation from June 2014 to July 2014.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave |